The term “escape hatches” is used in Transactional Analysis to describe the idea that when faced with very difficult or trying situations, some people exit the situation by carrying out one of three behaviours. These behaviours are to kill or harm self, kill or harm others or go crazy.

The term “escape hatches” is used in Transactional Analysis to describe the idea that when faced with very difficult or trying situations, some people exit the situation by carrying out one of three behaviours. These behaviours are to kill or harm self, kill or harm others or go crazy.

It’s normal practice for a transactional analyst to be listening out for talk of these four options when working with a client. It’s important that this talk is brought into awareness and discussed because the therapist has a responsibility to keep the client and those around the client safe. This duty of care requires that the therapist invites the client to close the escape hatch when it is detected.

How are escape hatches closed?

The usual way a therapist will close escape hatches is by asking the client to state clearly that they will not kill themselves/harm others/go crazy within a set period of time. This may be an agreement that they will not ever do this, or for those clients that are having very strong feelings, especially around suicide, they may contract to stay alive until the next session. The therapist can then contract with them in the new session for the next week, and progress week by week, hopefully moving the client on during the sessions to where the escape hatch can be closed on a longer term basis.

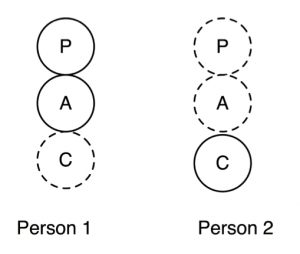

An important part of the escape hatch process is that the client is making a positive decision from an Adult place (an Adult ego state in TA terms) and is demonstrating to themselves that they have some power over their own lives. For some clients, who feel that they are at the whims and mercy of others, this may in itself be a big step.

Do we all have escape hatches?

I guess the answer to that is “yes”. Whether we allow ourselves to have them open or not is a different question. There is a difference between being aware of ways in which we deal with tragic situations and making that clear decision never to kill ourselves, harm others or go crazy. It also occurs to me that this decision may also change depending on our life circumstances. If you were diagnosed with a terminal illness and you knew you were going to face immense pain and discomfort as part of your demise could you honestly say that suicide would not be an option? It makes sense to me that people in such extreme circumstances would at least think such options through as a possibility.

Where do we make decisions around escape hatches?

Berne would say that the decision around whether to have our escape hatches open and which way we think is the best way of exiting is decided as part of our script. Script decisions are made early in life (between the ages of birth and six) and we spend the time from making them until early adulthood adjusting and refining them.

Other ideas around escape hatches.

Mark Widdowson, in his book “Transactional Analysis – 100 key points” talks about this idea that it’s often difficult to draw clear lines around escape hatches and I see his point. For me, as a psychotherapist, it’s easy to spot an open escape hatch if the client that is sat in front of me is talking about, say, suicide. I can intervene, talk it through with them and invite them to close the escape hatch. But how should I deal with a client that routinely overeats? What about smoking? These too are ways in which we do ourselves harm, albeit on a longer term less obvious basis.

As a therapist I believe it is my responsibility to point these methods of self-harm out too, but I may not contract with a client to change this behaviour specifically (ie, close this escape hatch).

Escape hatches are an interesting and important issue that therapists have to be aware of but, as with all things, are not necessarily as clear cut as they may first appear to be.

Do you have questions around escape hatches? Please let me know what you thought of this blog post and any opinions you have on escape hatches in the comment space below.

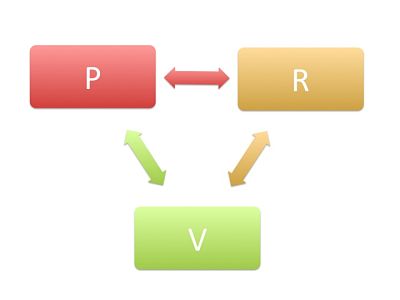

I’m not sure why it’s taken me so long to write about the Drama Triangle as it’s probably the concept that has had more “aha” factor than any of the others with my clients. People tend to “get it” and, as if by magic, the behaviour patterns that they have been engaged in with others suddenly become apparent. The concept also invites the client to think about the messages they learnt about themselves and others as they were growing up. This new awareness gives an ability to change and pull themselves out of unproductive ways of being.

I’m not sure why it’s taken me so long to write about the Drama Triangle as it’s probably the concept that has had more “aha” factor than any of the others with my clients. People tend to “get it” and, as if by magic, the behaviour patterns that they have been engaged in with others suddenly become apparent. The concept also invites the client to think about the messages they learnt about themselves and others as they were growing up. This new awareness gives an ability to change and pull themselves out of unproductive ways of being. The important thing to see here is those arrows going in both directions. When playing games an individual tends to move around the triangle taking all of the roles at different times. We dance around the triangle with our opposite number taking on all of the roles.

The important thing to see here is those arrows going in both directions. When playing games an individual tends to move around the triangle taking all of the roles at different times. We dance around the triangle with our opposite number taking on all of the roles. What is passivity?

What is passivity?