What is passivity?

What is passivity?

Passivity is when we put something off or don’t do it at all. It is an interesting and important subject when we are attempting to work out what makes humans tick.

I deal with clients displaying passive behavior pretty much every session I deliver therapy. Sometimes this may be a minor part of the problem, other times it can be the root of the issue. Passivity stops us growing, realizing our potential, confronting our fears and doing what we really want to do.

In this blog post I want to take passivity apart. I want to give you the theory (mostly taken from Aarron and Jacqui Schiffs paper “Passivity”, Jan 1971) and see how we can translate this to practical, doable steps for action. I want to do this because I am convinced that if we can confront and overcome our passive behavior then we can move towards happier, less frustrated, more fulfilled lives.

Understanding where passivity comes from.

The first stage of passivity is to understand symbiosis and in order to understand symbiosis you have to understand the ego state model that we use in transactional analysis. Fortunately I have already written a post on egostates that you can read here so check that out before reading further if you are not up on your “Parent, Adult and Childs”.

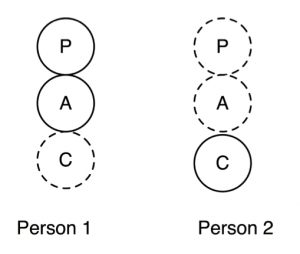

In symbiosis, the two people involved behave as if they are only one person from an egostate perspective. One individual will have an active Parent and Adult and the other will have an active Child. We diagram it like this;

Symbiosis is normal between mother and infant, and is important. The mother needs to be aware of the child’s needs and the child needs to know that the mother is there and will be cared for as he is completely dependent on the mother.

This way of relating is less effective when it is between you and your partner, or you and your boss once you are a fully functioning adult though yet it is surprisingly common and familiar to us all. A great example of it is those couples we all know who finish each other’s sentences or who carry out very clear roles within the relationship.

A useful example

Let me introduce you to Gladys and Jim. Gladys and Jim are a (fictious) married couple who have been together for years and slip into symbiosis at a drop of a hat.

Gladys carries out the practical duties to keep the house running, like cooking and cleaning and buying the groceries and Jim does almost nothing. Both Gladys and Jim enter into this arrangement comfortably and when it is questioned give “good reasons” for why their relationship is run like this.

Gladys would say “he’s useless, if I asked him to cook he would burn the kitchen down” and Jim would say “when I do get the shopping I buy the wrong thing so it’s best to let Gladys get on with it”.

Gladys and Jim also illustrate another two things that are needed in order to allow passivity; discounting and grandiosity.

Discounting

The Schiffs (1971) defined discounting as:

“the person who discounts believes, or acts as though he believes, that his feelings about what someone else has said, done or felt are more significant that what that person actually said, did or felt. He does not use information relevant to the situation.”

Let’s use our couple mentioned above to explain this in simple terms.

Gladys discounts Jim’s ability to cook even though when Gladys goes to look after her elderly mother for a week, Jim is perfectly able to prepare himself decent meals without causing house fires.

Jim discounts his ability to walk around the supermarket and read a simple list to ensure he does not buy the wrong thing. His belief that he cannot do this is bigger than the here and now reality that he is perfectly capable.

There are four ways in which we can discount:

- Discount the problem – I find a rash on my arm, and ignore it.

- Discount the significance of the problem – I find a rash on my arm, take a look and think “it’s nothing, it will go soon”.

- Discount the solvability of the problem – I find a rash on my arm and feel concerned but do nothing as “there is no medicine that will cure that”.

- Discount the person – I find a rash on my arm and feel concerned but do nothing because “no one will take any notice even if I did go to the doctors, there’s nothing I can do.”

Grandiosity

Grandiosity is the act of purposefully exaggerating about self or others or the environment in order to maintain the passivity. When we use grandiosity we take no responsibility for the decisions involved in a situation and we make the situation responsible for the behavior.

Grandiose language is easy to spot. Words like “always” and “never” can be heard and phrases like “I can’t stand it” “I was scared to death” or “I hit him because I was so furious”.

Jim may avoid going to the supermarket because “it is miles away” and Gladys may cook every night because if she doesn’t Jim will “starve to death”.

Why do we behave in this manner?

So why do we use discounting and grandiosity? The Schiffs say that we use discounting and grandiosity to remain in the passive symbiotic relationship with the other and not threaten the dependency contract. Jim and Gladys both have clear roles and know what they are supposed to do and where they stand. If Jim suddenly took over the cooking then this would threaten the Adult and Child ego states of Gladys and she would become agitated and uncomfortable. Equally, if Gladys expected Jim to go to the supermarket and buy the correct items this may cause him agitation or even anger as his dormant Adult and Parent ego states would be called into action.

Why is symbiosis bad?

The simple answer is that it is not always bad and can be an effective way for two people to function at times. The danger lies when we begin to discount our ability to change things that we don’t like and that are holding us back. It is this side of passivity that I see in my work with clients.

I see clients discount their ability to change their lives on a number of fronts. They discount the ability to change themselves, change their situation or can be grandiose about the response they will get if they change the situation.

5 suggestions for reducing your passivity

- Notice what’s going on – your clues are discounting and grandiosity. Are you using words like “always”, “never” “I/you can’t bear it” “I can’t cope”.

- Put things in perspective – you may feel nervous about doing things differently but what is really the worst that could happen? Are you being grandiose about the consequences of change?

- Look at your history – Are you used to thinking that you can’t do things or can’t change? You may have learnt this as a child and are carrying it into your adulthood. As a child it is tricky to change things because you do not have much power. The power lies with your parents. As an adult you have power. You can change your life and you are not reliant on anyone else to stay alive.

- Appreciate other adults will be OK – The adults in your life are just that, adults. Sometimes we have to make decisions that impact on others and that they won’t like but this choice is available to all adults and adults are self sufficient and can look after themselves.

- Work with a therapist – Therapists, (especially Transactional Analysists) are trained to spot discounting and grandiosity and will see symbiotic relationships you have formed with others. When this information is brought into your awareness you can choose what to do with it.

Tell me about your experiences with passivity

We all have passivity in our lives, it’s the amount and severity of the passivity we experience that can make a difference to how happy we are and how autonomous we feel. Please comment on the post below, how does passivity affect you in your life? Have you any good suggestions to help others with their passivity?

I’m sat here typing this at six o’clock in the morning in my pants. This may seem odd to many people but it makes perfect sense to me. This blog post will attempt to explain why I do (some of ) the things I do, and why knowing why I do the things I do helps me. I’m hoping that for you, once you start understanding why it’s good to work with someone who knows why you do the things YOU do (or at least is able to have an educated guess), you will see the benefit of working with a therapist.

I’m sat here typing this at six o’clock in the morning in my pants. This may seem odd to many people but it makes perfect sense to me. This blog post will attempt to explain why I do (some of ) the things I do, and why knowing why I do the things I do helps me. I’m hoping that for you, once you start understanding why it’s good to work with someone who knows why you do the things YOU do (or at least is able to have an educated guess), you will see the benefit of working with a therapist.